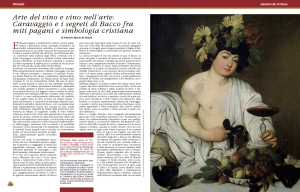

Art of wine and wine in the arts:

Caravaggio and the secrets of Bacchus, between pagan myths and christian symbols

Pagan thrill and mystical inebriation, eternal adolescence and divine youth, Hellenistic mythologies and erudite Catholic interpretations almost inextricably intertwine in one of the most memorable creations of European painting at the dawn of the seventeenth century, that charming Bacchus, stored in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence with which Caravaggio conquests the brilliant Roman aristocratic society by offering her a theme of classical allusion and, together, an intellectual repertoire of sacred and profane symbols of harmless modernity in the stylish circles of the papal city.

By merging with sensual virtuosity two apparently opposite and distant iconographic traditions, Caravaggio creates for his refined protector and patron, Cardinal Francesco Maria Bourbon Del Monte, powerful representative of Grand Duke Ferdinando I de ‘Medici at the Holy See, a work in which an amazing still-life portrait of a young man in theatrical pose is combined with an equally innovative Leonardo-Lombar matrix still-life, celebrating with crafty brilliance the incantatory almost magical power of a figure painting that deceives the senses and seduces the mind, conveying, at the same time, uplifting and unexpected Christian values.

The model’s realistically tanned face and hands, its nails black-rimmed, far too overripe fruit and almost rotting, that compose a manifestly symbolic vegetable anthology in front of the Bacchus, with a spectacular yet mercilessly buggy apple that slightly anticipates that of the famous Basket of Fruit of the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan; the masterful blown glass carafe half full of wine, where the light coming from the left beats peremptory, along with the chalice allusively offered by the young man to the by-now-enraptured spectator, with the garnet-colored liquid that flickers and describes concentric circles in the imminence of the homage, they dismiss all the variants and the expressive possibilities of an apparent instantaneity, which is composed of a remarkable theatrical form which reveals and conceals a painstaking study and a valuable duplicity of meanings, particularly appreciated by the erudite customer.

Once again, the extraordinary still life rendered with virtuous skill to deceive the eye and subdue the mind of the observer, fulfills, as it usually happens in the youngish works of Caravaggio, semantically eruditely interconnected multi-levels.

If it is true that the young Milanese painter had stated that it does not take lesser expertise to represent fruit and flowers than to portray the heads of saints, then the strict hierarchy of pictorial genres inevitably codified and passively accepted by masters and grubbers is, from this moment on, proudly subverted: Bacchus’ intensely suggestive face and gaze are no more important than the cup of wine in blown glass that the god offers to the viewer, and the superb split pomegranate or the quince turgid, haloed of fig leaves, have the same dignity and personality of the young Olympic man on the back.

The crown of vine leaves adorning the head of Bacchus, partially reddened and spotted with brown, attest the inexorable intense activity of Time, accompanied by small bunches of black and white grapes, transparent metaphor of death and resurrection, clearly covers same status of interest of the divine character, in a game of references between truth and symbol that forces the viewer to not consider any lower or less valuable image than the other in the economy of the canvas, and to inaugurate a new and all-encompassing vision mode, more outrageous and more modern which has been passed down to us intact.

Fine allegory of at least four of the five senses, where the taste of the wine and of the fruit does not obscure the touch, with a perfect rendering of velvety meat and clear glass surfaces, and the deceitfulness of sight, by virtue of the three-dimensional peremptory of the whole construction, it does not surrender to the solicitation of the many olfactory scents, between sweet and spicy, evoked by pulpy apples, overripe pears and purple figs that overflow from the ceramic fruit bowl cleverly staged by Caravaggio, the picture is also a valuable Christological metaphor certainly appreciated and perhaps addressed by the same Cardinal Del Monte, almost a riddle framework in accordance with the erudite taste of the era.

Bacchus, or rather Dionysus, where the original Greek name already evokes immediate similarities with the Christian foundations, was traditionally interpreted as an ideal foreshadowing or a mystical announcement of the Redeemer, in virtue of the story of death and rebirth that had sealed his fate when his mother Semele, who was ill-advised and had wanted to admire her lover Zeus in all his splendor, at all costs, had been burned by the supernatural light emanated from the father of the gods, and Zeus was quick to pull out from the womb of the unfortunate woman the little premature baby, to sew him in his thigh as an improvised incubator and re-bring him to life at the natural due date of birth, once perfectly healthy and formed.

Precisely this singular act of birth, along with the invention of Wine traditionally attributed to him, the elixir of Dionysus and blood of Christ together, had brought the most expert interpreters of the Renaissance Neoplatonism, still greatly in vogue in Italy and France, like Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, to finally convert to Christianity figure and attributes, seeing in the drunkenness propitiated by her drink a metaphor of that “Spiritual Drunkenness” of which the Fathers of the Church had already spoken of in their commentaries on the Song of Songs.

Protagonist of the famous poem, part of the Old Testament and traditionally attributed to Solomon, is the Bridegroom, who sings with intense lyricism his reciprocated love for the Bride, interpreted allegorically by the most erudite Christian exegetes as the absolute bond of love between Christ and his Church; and precisely the Bridegroom’s distinctive characteristics, his gentleness and his extenuated vagueness, his black hair in contrast with the milky complexion, celebrated by the bride with madly sensuous accents, and the analogy of the feeling itself with the delight of a ripe fruit, are embodied perfectly in the shape and features of Bacchus portrayed by Caravaggio:

“My beloved is fair and ruddy, chosen out of thousands. His curls are like clusters of palm, blacks as a raven … His arms are like spun gold, his bust is ivory … my beloved, among the young, is like an apple tree in the forest, and his fruit is sweet to my throat. Refresh me with flowers, sate me of apples and fruit … “.

Hair as black as a raven’s wing, candor of flesh, vagueness of looks, figs and pomegranates, apples and grapes constantly evoked and, along, the invitation to friends to drink from the cup at will:

“The fig tree has generated its fruits: the flourishing vines shed their fragrance. Arise my love, my fair one, and come on … I have drunk my wine with my milk: eat you too, o friends, drink and be drunken. “

“The mysterious cup”, commented in this regard St. Ambrose, “is like lathed by the author himself of our faith, that is the most perfect and always full of a spiritual and heavenly liquor. Since the Church has wine in its cup, which gladdens the heart of man. “

The two interconnected levels of interpretation: the most effectively pagan and profane one, and the Christian or Christian-inspired one, which blend without immoderate effort in the work of Caravaggio, especially if the model is the Bacchus – created by Leonardo around 1515 and soon replicated in fortunate copies certainly known to the Milanese painter, where the two interpretations are integrated with sophisticated ambiguity.

Leonardo had always represented an ineradicable ideal model to the young Caravaggio, either because of the almost obsessive attention to the truth of the lights and bodies, rigorously portrayed au naturelle, or either because of the brilliant actualization of the symbol, which is always embodied in an object evoked with extraordinary and deceptive realism; while from Caravaggio himself and from his exciting naturalistic research comes the magnificent canvas of Velazquez of 1629: The Triumph of Bacchus (The drunks) which declines with passionate theatricality but without erudite allegories the innovative verb of the Lombard master, putting it at the service of the picaresque literature that Francisco de Quevedo, Miguel de Cervantes and the anonymous author of Lazarillo de Tormes had elaborated as polemic response to the crystallized hierarchy of narrative genres, thus laying the secular and unscrupulous foundations of the modern novel.

The eight rogues with their unbuttoned doublet, threadbare cloak and dagger rogue on the kidneys, which make way to a Bacchus admittedly heir to Caravaggio’s, turn with comical devotion to the god, they offer a full glass, they bow to be crowned with branches of vine and look intently at the viewer, displaying marked faces and humble clothes far from the traditional norms of the decent and morally representable, thus inaugurating de facto, in the ultraconservative art of the Spanish court, the innovative and disruptive verb of the Truth at any cost.

Then also the refined Vermeer will play the card of the wine-transgression binomial, on the wave of brilliant Caravaggio-like realism, but with a crafty skill and a moralistic connotation, after all still in accordance with the Calvinist ethic of the time. Only the Lombard artist will know how to confer to his work that breath and that amazing duplicity, where religious and secular meet without rhetoric and without affectation, in an admirable alchemy that makes the Christian message so current and suggestively persuasive.

Once again, the black legend of an atheist and irreverent Caravaggio, sordid to the approach of the divine and eternally rebellious to Catholic orthodoxy, is revealed exactly for what it is: a slanderous and malicious interpretation, cleverly led by his contemporaries detractors and, together, the result of an arbitrary and updated interpretation which, by completely ignoring the Iconographic codes and the symbolic values widely shared and spread throughout the XVI and XVII centuries, revises in a pseudo-romantic way the work of the painter, well otherwise inspired by an aching and passionate religious tension, near the advocates of a poor church close to the suffering of the humble and the outcast, like the one promoted by Cardinal Federigo Borromeo or by St. Philip Blacks.

This does not subtract anything from the extraordinary and calibrated ambiguity of the work in question: the man is a true model with hands and face reddened by exposure to air and light, but it is also a perfect and allegorical Bacchus, the fruit partly attacked by time and by the pests is an authentic fruit and admirably represented, but also spectacular metaphor of the transience of earthly goods mercilessly corrupted by the prosaic passage of days, the light that enhances the whole three-dimensional scene is real soft light, but it’s also the Light of Truth and of Faith, in a clever and still unrepeatable game where the power of truth, human and Christian, is only secondary to the skill, the almost divine one, of an artist of incomparable grandeur.

Vittorio Maria de Bonis

Gallery not found. Please check your settings.